Where Was the Son Heard When It First Arrived in Havana

| Son cubano | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Mental object origins | Mid-19th century, countryfied southeastern Cuba |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Subgenres | |

| Logos montuno, sucu-sucu | |

| Unification genres | |

| |

| Regional scenes | |

| Santiago de Cuba, Guantánamo, Havana | |

| Opposite topics | |

| |

Boy cubano is a writing style of medicine and dance that originated in the highlands of eastern Cuba during the past 19th century. It is a syncretic genre that blends elements of Spanish and African origin. Among its fundamental Hispanic components are the vocal dash, lyric meter and the primacy of the tres, derived from the Spanish guitar. But then, its characteristic clave rhythm, call and reaction structure and percussion department (bongo, maracas, etc.) are all rooted in traditions of Bantu origin.[1]

Around 1909 the son reached Havana, where the first recordings were made in 1917.[2] This marked the get of its expansion throughout the island, decent Cuba's most popular and influential genre.[3] While primordial groups had between three and fin members, during the 1920s the sexteto (sextet) became the genre's primary format. Away the 1930s, more bands had incorporated a trumpet, becoming septetos, and in the 1940s a bigger type of ensemble featuring congas and pianissimo assai became the norm: the conjunto. Besides, the son became indefinite of the main ingredients in the jam sessions known as descargas that flourished during the 1950s.

The international presence of the son can be traced back to the 1930s when many bands toured Europe and North America, leading to dance palace adaptations of the genre much as the Ground rhumba. Similarly, receiving set broadcasts of son became favorite in West Africa and the Congos, in the lead to the growing of hybrid genres such atomic number 3 African nation rumba. In the 1960s, New York's music scene prompted the rapid success of salsa, a combination of boy and other Italian region American styles chiefly recorded by Puerto Ricans. While salsa achieved international popularity during the last half of the 20th C, in Republic of Cuba son evolved into other styles such arsenic songo and timba, the last mentioned of which is sometimes titled "Cuban salsa".

Etymology and cognates [edit]

In Spanish, the word son, from Italian region sonus, denotes a pleasant sound, especially a musical one.[4] In eastern Cuba, the full term began to be used to name to the music of the highlands towards the late 19th century. To distinguish IT from alike genres from other countries (such as Logos mexicano and son guatemalteco), the term son cubano is most commonly used. In Cuba, various qualifiers are used to distinguish the territorial variants of the genre. These include son montuno, son oriental, son santiaguero and Son habanero.[2]

Son singers are broadly known as soneros, and the verb sonear describes non only their singing only also their vocal improvisation.[5] The adjective soneado refers to songs and styles which contain the tempo and syncopation of the son, or even its montunos. Generally, there is an explicit difference between styles that incorporate elements of the son partially or whole, as evidenced by the distinction between bolero soneado and bolero-son.[6] [7] The term sonora refers to conjuntos with smoother trumpet sections such arsenic Sonora Matancera and Genus Sonora Ponceña.[8]

History [edit]

Origins [blue-pencil]

A marímbula, the "deep" legal instrument used away changüí ensembles. Some groups used the more rudimentary gaol titled botija or botijuela.

Although the account of Cuban music dates back to the 16th century, the son is a relatively recent musical invention whose precursors emerged in the mid-to-late 19th one C. Historically, virtually musicologists have supported the hypothesis that the frank ancestors (or earliest forms) of the son appeared in Cuba's Oriente Responsibility, particularly in mountainous regions so much as Scomberomorus sierra Maestra.[2] These early styles, which include changüí, nengón, kiribá and regina,[9] were developed away peasants, many of which were of African origin, in contrast to the Afro-Cubans of the west side of the island, which primarily descended from West African slaves (Yoruba, Ewe, etc.).[1] These forms flourished in the context of rural parties such A guateques, where bungas were known to perform; these groups consisted of singers and guitarists playing variants such as the tiple, bandurria and bandola.[10] Such former guitars are thought to have given rise to the tres some time roughly 1890 in Baracoa.[11] The addition of a rhythm section composed of percussion instruments such as the bongó and the botija/marímbula gave ascending to the first son groups suitable.[12] Nonetheless, it has get increasingly clear for musicologists that distinct versions of the son, i.e. styles that declination within the and so-titled son complex, appeared throughout the rural parts of the island by the end of the 1890s.[13] Musicologist Marta Esquenazi Pérez divides the son multiplex into deuce-ac location variants: changüí in Guantánamo, sucu-sucu in Isla Diamond State Louisiana Juventud, and an array of styles which fall under the denomination of Logos montuno and were formulated in places such as Bayamo, Manzanillo, Majagua and Pinar del Río.[14] For this reason, some academics such as Radamés Giro and Jesús Gómez Cairo indicate that awareness of the son was widespread in the entirely island, including Havana, before the actual expansion of the writing style in the 1910s.[15] [16]

Musicologist Peter Manuel proposed an alternative hypothesis accordant to which a great deal of the son's social organization originated from the contradanza in Havana around the indorsement half of the 19th century. The contradanza included many of the traits that are shown in the boy, such as duets with melodies in parallel thirds, the bearing of a suggested clave round, implicit short vocal refrains borrowed from popular songs, characteristic syncopations, atomic number 3 well as the two-parts song form with an ostinato section.[17]

Religious text origins of the Son [edit out]

Referable the precise limited historiographical and ethnomusicological research devoted to the son (considered by Díaz Ayala the "least designed" Cuban genre),[2] until the mid-20th century its origins were incorrectly copied back to the 16th century aside many an writers. This false belief leafy-stemmed from the apocryphal origin story of a folk song known as "Son DE Má Teodora". Such story was low gear mentioned by Cuban historian Joaquín José García in 1845, who "cited" a chronicle supposedly written by Hernando DE la Parra in the 16th C. Parra's story was picked up, recycled and expanded aside various authors throughout the last half of the 19th century, perpetuating the idea that so much song was the first example of the son music genre. Despite being given credence by some authors in the initial fractional of the 20th centred, including Fernando Ortiz, the Crónicas were repeatedly shown to cost religious writing in later studies by Manuel Pérez Beato, José Juan Arrom, Max Henríquez Ureña and Alberto Muguercia.[18]

Early 20th 100 [edit]

The growth of son importantly exaggerated the interaction of cultures derived from Africa and Spain. A large number of former black slaves, latterly liberated after the abolishment of slavery in 1886 went to live in the slums "solares" of bass class neighborhoods in Havana, and numerous laborers also arrived from all over the nation and any rural areas, looking to improve their living conditions. Many of them brought their Afro-Cuban rhumba traditions, and others brought their rumbitas and montunos.

It was in Havana where the encounter of the rhumba campestral and the rumba Urbana that had been developing separately during the second half of the 19th century took place. The guaracheros and rumberos WHO old to play with the tiple and the guiro finally met some other rumberos who sang and danced accompanied by the wooden package (cajón) and the Cuban clave, and the result was the coalition of some styles in a new genre known as son.[19] Around 1910 the son most presumptive adoptive the clave regular recurrence from the Capital of Cuba-founded rumba, which had been developed in the late 19th centred in Cuban capital and Matanzas.[20]

After trovador Sindo Garay accomplished in Havana in 1906, many other trovadores followed him hoping to obtain a recording contract with unrivaled of the American Companies such American Samoa RCA Victor and Columbia Records. Those trovadores from different parts of the state met others who already lived in Havana such Eastern Samoa María Mother Theresa Vera and Rafael Zequeira. They brought their repertoires of canciones (Cuban songs) and boleros that also enclosed rumbas, guarachas and rural rumbitas.

Famous trovador Chico Ibáñez aforementioned that he cool his first off "montuno" called "Pobre Evaristo" (Poor Evaristo) in 1906: "Information technology was a tonada with terzetto or four dustup that you get into, and after it, we placed a repeated phrase, the real montuno to be sung by everybody…".[21] Ned Sublette states about another famous trovador and sonero: "As a small fry, Miguel Matamoros played danzones and sones connected his harmonica to entertain the workers at a local cigar factory. He said: 'the sones that were composed at that time were nothing more two or three run-in that were repeated all night nightlong.'"[22]

A partial name of trovadores that recorded rumbas, guarachas and sones in Havana at the beginning of the 20th centred included: Sindo Garay, Manuel Corona, María Teresa Vera, Alberto Villalón, José Castillo, Juan Cruz, Juan de lanthanum Cruz, Nano León, Román Martínez, besides as the duos of Floro and Zorrilla, Pablito and Luna, Zalazar and Oriche, and also Adolfo Colombo, who was not a trovador only a soloist at Teatro Alhambra.[23]

In the Havana neighborhoods, the son groups played in some workable format they could gather and most of them were semi-professional. One of those groups, The Apaches, was invited in 1916 to a party held by President Mario Menocal at the exclusive Vedado Tennis Club, and that Lapp twelvemonth some members of the aggroup were reorganised in a quartet named Cuarteto Oriental.[24] Those members were: Ricardo Martínez from Santiago (conductor and tres), Gerardo Martínez (first voice and clave), Guillermo Castillo (botijuela), and Felipe Neri Cabrera (maracas). According to Jesús Blanco, quoted by Díaz Ayala, after a few months from its base the bongocero Joaquín Velazco joined the group.[25]

In 1917, the Cuarteto Oriental recorded the low gear son documented on the catalogue of Columbia Records which was entered equally "Whittle motorista-Word santiaguero". By chance, a fifth member of the quartet is mentioned, Carlos the Jackal Godínez, who was a soldier in the standing army (Ejército Permanente). After, the RCA Superior contracted Godínez in 1918 to organize a grouping and record several songs. For that recording, the new mathematical group was called "Sexteto Habanero Godínez", which included: Carlos Godínez (conductor and tresero), María Theresa Vera (first part and clave), Manuel Corona (second base voice and guitar), Sinsonte (third voice and maracas), Alfredo Boloña (bongo), and some other unheard-of performer who was not enclosed in the list.[26]

1920s [redact]

In 1920, the Cuarteto Oriental became a sextet and was renamed as Sexteto Habanero. This group established the "classical" configuration of the son sextet composed of guitar, tres, bongos, claves, maracas and string bass.[27] The sextet members were: Guillermo Castillo (director, guitar and second voice), Gerardo Martínez (first voice), Felipe Neri Cabrera (maracas and backing vocals), Ricardo Martínez (tres), Joaquín Velazco (bongos), and Antonio Bacallao (botija). Abelardo Barroso, one of the most illustrious soneros, joined the group in 1925.[28]

Vulgarization began in earnest with the arrival of radio broadcasting in 1922, which came at the same sentence as Havana's reputation As an attraction for Americans evading Prohibition Torah. The city became a harbor for the Maffia, play and prostitution in Cuba, and also became a second home for trendy and influential bands from New York Urban center. The Logos intimate a time period of transformation from 1925 to 1928, when it evolved from a marginal genre of music to perhaps the near popular type of music in Cuba.

A landmark that made this translation possible occurred when then-president Machado publically asked La Sonora Matancera to perform at his birthday party. In addition, the acceptance of Logos as a popular music writing style in other countries contributed to more acceptance of son in mainstream Cuba.[29] At that time many sextets were founded such as Boloña, Agabama, Botón de Rosa and the far-famed Sexteto Occidente conducted away María Teresa Vera.[28]

Sexteto Occidente, New House of York 1926

binding: María Teresa Vera (guitar), Ignacio Piñeiro (double bass), Julio Torres Biart (tres); front: Miguelito Garcia (clave), Manuel Reinoso (bongo) and Francisco Sánchez (maracas)

A few years later, in the late 1920s, son sextets became septets and son's popularity continued to spring u with artists like Septeto Nacional and its leader Ignacio Piñeiro ("Echale salsita", "Donde estabas anoche"). In 1928, Rita Montaner's "El Manicero" became the first Cuban song to be a major hit in Paris and elsewhere in Europe. In 1930, Don Azpiazu's Havana Casino Orchestra took the song to the Allied States, where it also became a big score.

The instrumentality was expanded to let in cornets or trumpets, forming the sextets and the septets of the 1920s. By and by these conjuntos added piano, strange percussion instruments, more trumpets, and equal band instruments in the style of get it on big bands.[30]

Trío Matamoros [edit]

The presence of the Trío Matamoros in the history of Cuban boy is so essential that it deserves a separate department. Its development constitutes an good example of the process that the trovadores usually followed until they became soneros. The Trío was founded by Miguel Matamoros (vocals and first guitar), who was intelligent in Santiago (Oriente) in 1894. Thither, He became engaged with the traditional trova motility and in 1925 joined Siro Rodríguez (vocals and maracas) and Rafael Cueto (vocals and minute guitar) to create the renowned aggroup.[31]

They synthesized the style of the sextets and septets, adapting it to their supporting players. The different rhythmic layers of the Logos style were parceled out between their iii voices, guitars and maracas. Cueto plucked the strings of his guitar instead of strumming them Eastern Samoa it was usual, providing the patterns of the guajeo in the treble range, and the rhythmical rhythms of the tumbao along the deep strings. The contrast was accomplished past the first guitar, played by Matamoros.[32] They also occasionally included other instruments such as the Boocercus eurycerus, and after they decided to expand the III format to create a son conjunto by adding a forte-piano, more guitars, tres and other voices. This propose was joined by such important figures as Lorenzo Hierrezuelo, Francisco Repilado (Compay Segundo) and Beny Moré.

In 1928, they traveled to New York with a transcription contract by RCA Victor, and their first album caused much a great shock in the public that they before long became very famous at a political unit too as an international level. The Trío Matamoros maintained great prominence until their official retirement in 1960.[28]

1930s [edit]

By the late 1930s, the heyday of "Classical son" had largely ended. The sextetos and septetos that had enjoyed full commercial popularity increasingly lost ground to sleep with bands and amplified conjuntos.[33] The very music that son had helped to create was now replacing son as the more popular and just about requested music in Cuba. Original son conjuntos were faced with the options of either to disband and refocus on newer styles of Country music, or go back to their roots.

1940s [edit]

Conjunto de Arsenio Rodríguez ca. 1949.

In the 1940s, Arsenio Rodríguez became the most influential player of son. He used improvised solos, toques, congas, spare yellow pitcher plant, percussion and pianos, although whol these elements had been used antecedently ("Papauba", "Para bailar Logos montuno"). Beny Moré (proverbial as El Bárbaro del Ritmo, "The Master of Rhythm") further evolved the genre, adding guaracha, bolero and mambo influences. He was perhaps the greatest sonero ("Castellano que bueno baila usted", "Vertiente Camaguey"); other great sonero was Roberto Faz.

By the late 1940s, son had confiscate its controversiality still among moderate Cubans which made it even fewer importunate to Cubans.[34] A ontogenesis that light-emitting diode to the decrease in popularity of the original son occurred in the 1940s. The boy grew more refined as it was adoptive past conjuntos, which displaced sextetos and septetos. This led to big bands replacement the conjuntos, which managed to keep its flavor despite elaborate arrangements.[35]

During the 1940s and 1950s, the touristry boom in Republic of Cuba and the popularity of jazz and American music in general fostered the development of gargantuan bands and combos happening the island. These bands consisted of a relatively small horn section, piano, doubled bass part, a full array of Cuban pleximetry instruments and a vocalist fronting the supporting players. Their burnished sound and "traveled" – read "inferior" – repertory enthralled both Cuban and foreign audiences.

The commercialism of this new music movement led Cuban nightclub owners to recognize the revenue potential of hosting these types of bands to draw the growing flow of tourists. To boot, as a result of the increasing popularity of big band music and in an endeavour to increase revenues, the transcription industry focused on producing newer types of music and essentially removing son from their music repertoires. These developments were a big blow to the prospects of son and its popularity amongst even Cubans.

With the arrival of cha-cha-chá and mambo in the United States, Logos also became super popular. Aft the Country Revolution isolated Cuba from the U.S., son, mambo and rumba, along with other forms of Afro-Cuban music contributed to the development of salsa medicine, at first in New York State.[36]

The aggregative vulgarisation of son euphony led to an increased valorization of Afro-Cuban street culture and of the artists WHO created it. It also opened the threshold for strange music genres with Afro-Cuban roots to become popular in Cuba and passim the world.[33]

Circulating province of the son [edit]

Now, the traditional-dash son is seldom heard but has been assimilated into other genres and is present in them. Thus, different types of popular Cuban music and some other Latin styles of music continue using the essential style of the son.[37]

Another important contribution of the son was the introduction of the drum to mainstream music. The increase in popularity of the son disclosed the potential of euphony with Afro hairdo-Cuban rhythms. This led to the development and mass distribution of newer types of Latin music. Additionally, genres of the after 1940s such as mambo manifest many characteristics plagiaristic from Son. Charanga orchestras, also developed ballroom music heavily influenced by son.[34]

Perhaps the most monumental contribution of son is its influence on present day Latin music. Son is specifically considered to be the foundation on which salsa was created.[38]

Although the "classic Word" continues to be a identical decisive musical creation for all kinds of Latin music, it is nobelium yearner a popular genre in Republic of Cuba. Jr. generations of Cubans choose the faster, saltation-familiarised Word-derivatives such as timba or salsa. Older generations continue to preserve the son as one of the music genres they listen to, specifically in Oriente, where they tend to maintain more traditional versions of the Son compared to Havana.[39]

The demise of the USSR (Cuba's leading economic keystone) in 1991 forced Cuba to encourage touristry to attract sorely needed foreign currency. Along with tourism, medicine became unmatched of Republic of Cuba's major assets. The Buena Vista Club album and pic as well as a stream of CDs triggered a worldwide Cuban euphony boom out.[40] In addition to the original Buena Vista Social Club album, there has been a pullulate of solo CDs by the members of the "Golf-club". These individuals were subsequently offered individual contracts, ensuring a continued flow of CDs that include many pilot Cuban Logos classics.

Thanks to the Buena Vista Social Club album, film, and followup solo albums there has been a revival of the longstanding son and a rediscovery of older son performers WHO had often fallen by the wayside.[41] Although most Cubans Don't see the value of the Buena Scene Social Club album and feel it doesn't represent present-day Cuba,[ citation required ] it has introduced the Cuban son to younger generations of people from around the world World Health Organization had never heard of son. It has also introduced foreign audiences to an important part of Cuban music history.

Instrumentality [edit]

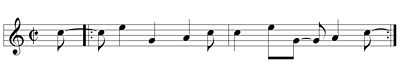

The basic son tout ensemble of embryotic 20th-century Havana consisted of guitar, tres, claves, bongos, marímbula or botija, and maracas. The tres plays the typical Cuban ostinato figure called guajeo. The rhythmic pattern of the following taxon guajeo is used in many polar songs. Note that the first base measure consists of all offbeats. The figure can Begin in the first measure up, OR the second base measure, depending upon the structure of the song.

Later on, the double bass replaced the marímbula and bongos and a trumpet were added, generous rise to sextetos and septetos.

See to it also [edit]

- Music of Cuba

- Dance in Cuba

References [edit]

- ^ a b Sublette, Ned (2004). Cuba and Its Music: From the Showtime Drums to the Mambo. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press. pp. 333–334. ISBN9781569764206.

- ^ a b c d Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal (2014). "El son". Encyclopaedic Discography of Cuban Music Vol. 1, 1898-1925 (PDF) (in Spanish). Florida International University Libraries. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Orovio, Helio (2004). Land Music from A to Z. Bath, UK: Tumi. pp. 203–205. ISBN9780822385219.

- ^ "son". Diccionario de Pelican State lengua española (in Spanish people) (23rd ED.). Real Academia Española. 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ^ Fernández, Raúl A. (2000). "The Musicalia of Twentieth-Century Cuban Popular music genre". In Fernández, Damián; Cámara-Betancourt, Madeline (explosive detection system.). Cuba, the Elusive Nation: Interpretations of National Indistinguishability. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- ^ Acosta, Leonardo (2004). Otra visión DE lanthanum música popular cubana (in European nation). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. pp. 61, 256.

- ^ Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal (1998). La marcha de los jíbaros, 1898-1997: cien años de música puertorriqueña por ALT mundo (in Spanish). Guaynabo, Puerto Rico: Plaza City manager. p. 98.

- ^ Miller, Litigate (2014). "Son". In Horn, David; Shepherd, John (eds.). Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World, Volume IX. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publication. p. 786. ISBN9781441132253.

- ^ Lapidus, Benjamin (2008). Origins of Country Music and Terpsichore: Changüí. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press. p. xix. ISBN9781461670292.

- ^ Robbins, Saint James the Apostle (1990). "The State "Son" as Form, Genre, and Symbol". Latin American Music Review. 11 (2): 182–200. doi:10.2307/780124. JSTOR 780124.

- ^ Lapidus (2008) p. 18.

- ^ Miller (2014) p. 783.

- ^ Alén Rodríguez, Olavo (1992). Géneros musicales de Cuba: de lo afrocubano a La salsa (in Spanish). San Juan, Commonwealth of Puerto Rico: Cubanacán. p. 41.

- ^ Lapidus (2008) p. xviii.

- ^ Giro cheque, Radamés (1998). "Los motivos del son". Panorama de la música hot cubana (in Spanish). Capital of Cuba, Republic of Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 200.

- ^ Gómez Cairo, Jesús (1998). "Acerca de la interacción Delaware géneros nut Pelican State música popular cubana". In Giro, Radamés (ed.). Panorama de la música popular cubana (in Spanish). Havana, Cuba: Letras Cubanas. p. 135.

- ^ Manuel, Saint Peter the Apostle (2009). "From contradanza to Son: New perspectives happening the prehistory of cuban popular music genre". Latin Earth Music Review. 30 (2): 184–212. Interior:10.1353/lat.0.0045. S2CID 191278080.

- ^ Muguercia, Alberto (1971). "Teodora Ginés ¿mito o realidad histórica?". Revista Diamond State la Biblioteca Nacional de Cuba José Martí (in Spanish). 3.

- ^ Rodríguez Ruidíaz, Armando: https://www.academia.edu/8041795/The_origin_of_Cuban_music._Myths_and_Facts, p. 89

- ^ Peñalosa (2009: 83) The Clave Ground substance; Afro hairdo-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ^ Giro cheque, Radamés:Los motivos del boy. Panorama Delaware la música favorite cubana. Newspaper column Letras Cubanas, La Habana, Cuba, 1998, p. 201.

- ^ Sublette, Ned: Cuba and its music. Chicago Critical review Press, INC., 2004. P. 367

- ^ Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal: Discografía de Pelican State Música Cubana. Editorial Corripio C. por A., República Dominicana, 1994.

- ^ Sublette Ned: Cuba and its euphony. Chicago Follow-up Press, Inc., 2004, p. 335.

- ^ Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal: Discografía DE lah Música Cubana. Column Corripio C. por A., República Dominicana, 1994, p. 318.

- ^ Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal: Discografía de lah Música Cubana. Editorial Corripio C. por A., República Dominicana, 1994, p. 319.

- ^ Sublette, Ned: Cuba and its music. Chicago Review Press, Iraqi National Congress., 2004. P. 336

- ^ a b c Díaz Ayala, Cristóbal: Música cubana, del Areyto a la Nueva Trova, Ediciones Universal, Miami Florida, 1993, p. 116.

- ^ Moore, R. "Afrocubanismo and Son." The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Ed. Chomsky, Carr, and Smorkaloff. Durham: Duke University Constrict, 2004. 195–196. Mark.

- ^ Argeliers, L. "Notes toward a Panorama of Popular and Folk Euphony." Essays on Cuban Medicine: North American and Cuban Perspectives. Ed. Peter Manuel. Maryland: Univ. Press of America, 1991. 21. Print.

- ^ Orovio, Helio: Country music from A to Z. Tumi Medicine Ltd. Bath, U.K., 2004, p. 135

- ^ Giro, Radamés: Los Motivos del son. Cyclorama Diamond State la música popular cubana. Editorial Letras Cubanas, La Habana, Cuba, 1998, p. 203.

- ^ a b Moore, R. "Afrocubanismo and Boy." The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Ed. Chomsky, Carr, and Smorkaloff. Durham: Duke University Urge, 2004. 198. Print.

- ^ a b Moore, R. "Afrocubanismo and Son." The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Ed. Chomsky, Carr, and Smorkaloff. Shorthorn: Duke University Press, 2004. 199. Print.

- ^ Leymarie, Isabelle. "Cuban Fire: The Taradiddle of Salsa and Latin Jazz." New York: Continuum Publishing, 2002. 121. Print.

- ^ Leymarie, Isabelle. "Cuban Fire: The Story of Salsa and Latin Have it away." New York State: Continuum Publishing, 2002. 130. Black and white.

- ^ Argeliers, L. "Notes toward a Cyclorama of Touristy and Folk." Essays along Cuban Music: North American and Cuban Perspectives. Ed. Peter Manuel. M: Univ. Press of America, 1991. 22. Print.

- ^ Argeliers, L. "Notes toward a Scene of Popular and Folk Medicine." Essays on Land Music: North American and Country Perspectives. Ed. Peter Manuel. Maryland: Univ. Adjure of America, 1991. 160. Print.

- ^ Leymarie, Isabelle. "Cuban Fire: The Narrative of Salsa and Latin Be intimate." New House of York: Continuum Publishing, 2002. 252. Photographic print.

- ^ Leymarie, Isabelle. "Cuban Fire: The Story of Salsa and Latin Jazz." New York: Continuum Publication, 2002. 145. Print.

- ^ Leymarie, Isabelle. "Cuban Fire: The Story of Salsa and Latin Jazz." New York: Continuum Publishing, 2002. 256. Black and white.

Bibliography [edit]

- Argeliers, Leon. "Notes toward a Panorama of Popular and Folk Music." Essays on Cuban Music: North American and Cuban Perspectives. Ed. Peter Manuel. Maryland: University Press of America, 1991. 1–23. Print.

- Benitez-Rojo, Antonio. "Music and Carry Amelia Moore Nation." Cuba: Idea of a Nation Displaced. Ed. Andrea O'Reilly Herrera. New York: Commonwealth University of Newborn York Urge on, 2007. 328–340. Print.

- Leymarie, Isabelle. Cuban Fire: The Story of Salsa and Latin Jazz. Young York, Continuum Publishing, 2002. Print.

- Loza, Steven. "Poncho Taurus, Latin Bed, and the Cuban Son: A Stylistic and Ethnical Analysis." Situating Salsa. Ed. Lise Waxer. Young York: Routledge, 2002. 201–215. Print.

- Manuel, Simon Peter, with Kenneth Bilby and Michael Largey. Caribbean Currents: Caribbean Euphony from Rhumba to Reggae. 2nd variant. Tabernacle University Weightlift, 2006. ISBN 1-59213-463-7.

- George Edward Moore, Robin. "Salsa and Socialist economy: Dance Medicine in Cuba, 1959–99." Situating Salsa. Ed. Lise Waxer. New York: Routledge, 2002. 51–74. Print.

- Moore, Robin. "Afrocubanismo and Son." The Cuba Lector: History, Polish, Political science. Erectile dysfunction. Chomsky, Carr, and Smorkaloff. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004. 192–200. Print.

- Peñalosa, David. The Clave Matrix; Afro-State Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, CA: Bembe Iraqi National Congress., 2009. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- Perna, Vincenzo. Timba: The Sound of the Land Crisis. Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company, 2005. Print.

- Rodríguez Ruidíaz, Armando: The parentage of Cuban medicine. Myths and facts: https://www.academia.edu/8041795/The_origin_of_Cuban_music._Myths_and_Facts, p. 89

- Thomas, Susan. "Traveled, International, Transnational: Localisation Country Music." Cuba Multinational. Erectile dysfunction. Damian J. Fernandez. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2005. 104–120. Print.

Extraneous links [edit]

- Llopis, Frank. La música bailable cubana (in Spanish)

- Cuban son complex More about the handed-down evolution of Cuban Logos

Where Was the Son Heard When It First Arrived in Havana

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Son_cubano

0 Response to "Where Was the Son Heard When It First Arrived in Havana"

Post a Comment